Can we imagine a

world without white eyes?

‘What would it mean for whites, and white photographers,

to accept that we see with a white racist eye?’

to accept that we see with a white racist eye?’

Whiteness was invented in the 17th century as a system of social control. As early as 1619, in British colonies such as Jamestown, Virginia, the eventual construction of whiteness began with the arrival of the first twenty African slaves. The British sought to divide humans along the lines of skin color — white European colonizers at the top, followed by white workers, with Black slaves and Brown Native Americans at the bottom. For over four-hundred years, beginning with a violent idea and developing into a fully blown pseudoscience, this system of racial difference has continued. ‘Race’ is a fiction authored by whites, but for people of color it is a nonsense with very real consequences indeed.

In what we now call ‘the West’, politics, business, justice, healthcare, education and culture are all white dominated. Whiteness is alive and well, yet we are seldom taught about its history. We white people are ignorant of a system we created, seeing ourselves as racially ‘neutral’ because we benefit from our own invention. Our bodies and minds are subject to social and psychological processes that interpellate us into whiteness. We internalize a false logic of racial difference, yet it has no biological or genetic basis. We take a social idea and allow it to govern how we live, and crucially, how we see. It is a myth that we live in ‘post-racial’ societies.

While understanding whiteness and race as social and legal inventions, I consider it important to understand whiteness as something nevertheless visual. White people ‘gaze,’ but we do not always see. Cultural theorist Stuart Hall called this the ‘white eye’. We whites are blind to the dominance of white visuality and we can understand this most clearly with the invention and popularization of photography, which is a visual world white people created in our own image.

What if the canonical history of photography — emerging in the 1830s some two-hundred years after whiteness — is best understood, not as an objective ‘history of pictures,’ but as a history of white visuality, even white visual racism? What if the camera is the logical extension of the white eye? After all, it’s not just the ‘race’ of the person who uses the camera that governs its way of gazing, it’s also the very materials used to make the pictures. What would it mean for whites, and white photographers, to accept that we see with a white racist eye? Furthermore, as the identity of whiteness was born out of a form of social violence, what if to be white is to be racist? I believe these are complex social and psychological questions that must be taken seriously if we are to create a truly fair and equal world. There is no good whiteness.

In order to untie ourselves from whiteness, and from white dominant photographic practices, we need to subvert what I call ‘the image of whiteness.’ This would be the very act of rendering ourselves open and vulnerable to the reality of whiteness, while at the same time attacking the logic of its image. Images are, after all, forms of imagination — so why can’t we imagine a world without whiteness, without white eyes?

In the hope that we might get there someday, let’s consider how contemporary photographic art on the subject of whiteness, in its varying subtleties and guises, can be put to use as a form of subversion, or disruption. A rebuttal to white visual culture. As Yasmin Gunaratnam has asked, how can photographic images “detain” or reveal whiteness? How might photography be reclaimed from its own history, in order to help white people see anew?

Michelle Dizon & Viêt Lê

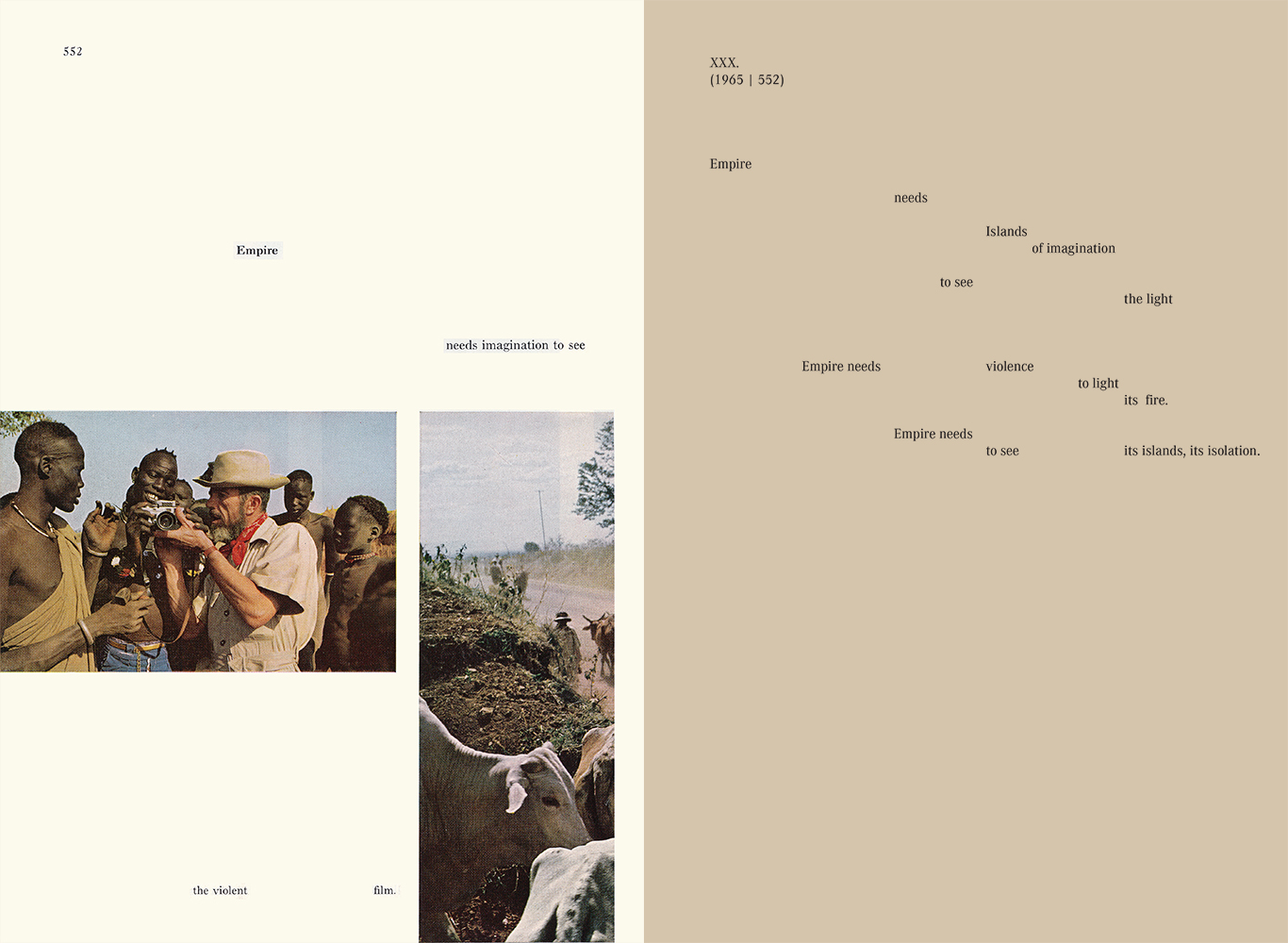

![Michelle Dizon & Viêt Lê, White Gaze (book spread), 2018. Courtesy the artists and Sming Sming Books.]() Michelle Dizon & Viêt Lê, White Gaze (book spread), 2018. Courtesy the artists and Sming Sming Books.

Michelle Dizon & Viêt Lê, White Gaze (book spread), 2018. Courtesy the artists and Sming Sming Books.

Michelle Dizon and Viêt Lê’s White Gaze bookproject sees the artists appropriate photographs from the National Geographic archive and put them to anti-racist use. The American magazine has a long history of racist visual overtones that place people of colour in a subjugated relationship to the ethnographic and imperial gaze of white western photographers. The artists juxtapose images with concrete poetry to create image-text intersections that reveal and critique visual cultures of whiteness, the white eye, and its forms of privileged looking. Of the project, Michelle Dizon writes: “There are certainly a lot of images where the camera is present, or where a white photographer took a picture within a specific context. Where there is looking, it’s usually a very gendered looking, and those forms of gendered violence across the bodies of both colonized women and men run throughout these images.”

Ken Gonzalez-Day

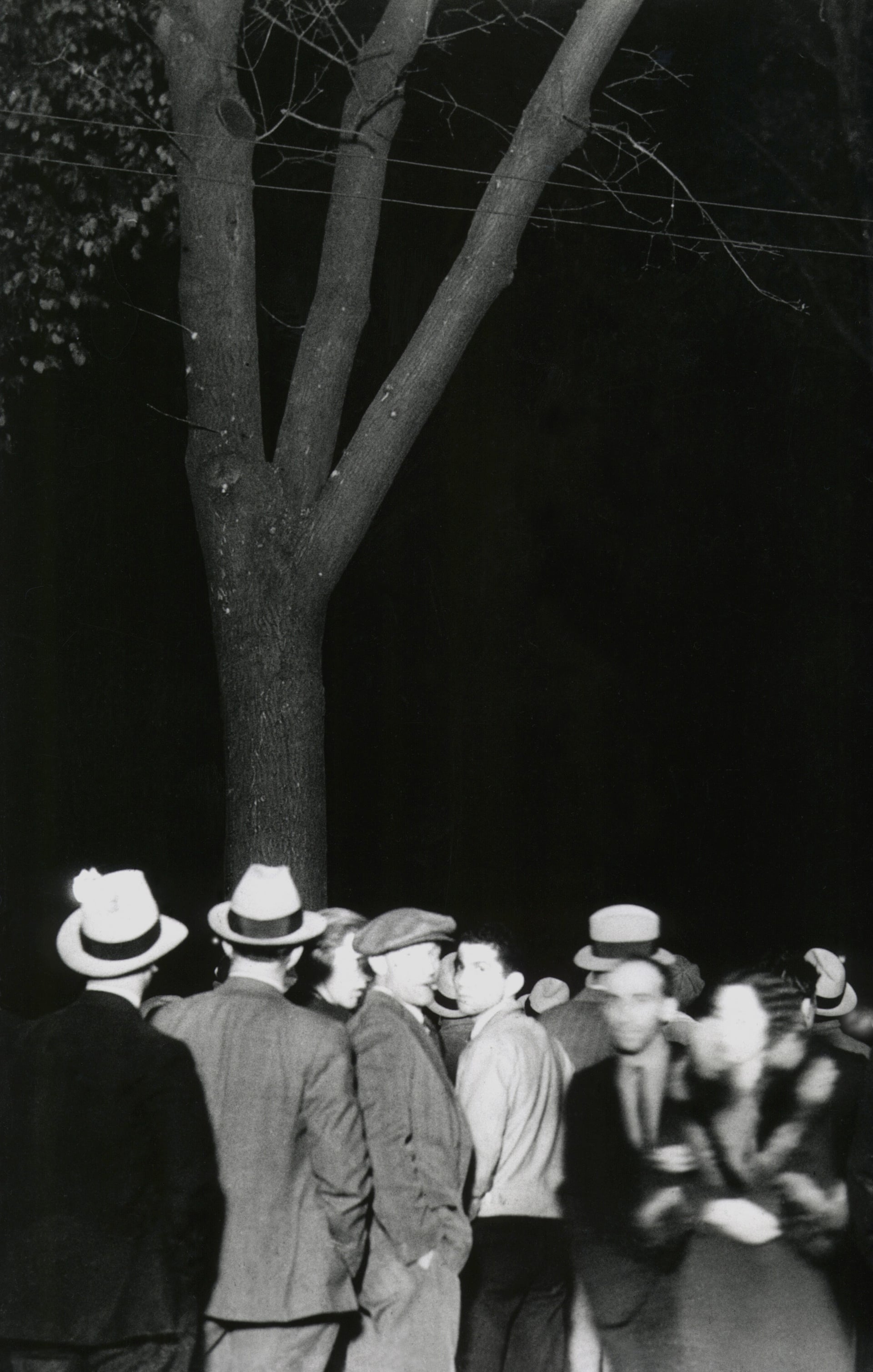

![]() Ken Gonzales-Day, East First Street #2 (St. James Park), from the series Erased Lynchings, 2013. Courtesy the artist and Luis De Jesus Los Angeles.

Ken Gonzales-Day, East First Street #2 (St. James Park), from the series Erased Lynchings, 2013. Courtesy the artist and Luis De Jesus Los Angeles.

Ken Gonzalez-Day’s images from the series Erased Lynchings sees the artist digitally remove the dead and hanging body of a nameless murdered person of colour, in order to avoid re-victimising the individual. This places our attention on the real guilty subjects, those white people who take it upon themselves extrajudicially to police Black and Brown bodies. The Black body is here removed from the gaze of white eyes, a form of sight which undergirds the social dominance of whiteness. Gonzales-Day writes on his website: “The work asks viewers to consider the crowd, the spectacle, the role of the photographer, and even the impact of flash photography, and their various contributions to our understanding of racialized violence in this Nation.”

Hank Willis Thomas

![]() Hank Willis Thomas, Wipe Away the Years, 1932/2015, from the series Unbranded: A Century of White Women, 1915-2015. Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Hank Willis Thomas, Wipe Away the Years, 1932/2015, from the series Unbranded: A Century of White Women, 1915-2015. Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Hank Willis Thomas’s works Unbranded: A Century of White Women, 1915-2015, are made by appropriating old advertisements and removing logos and text. What remains are images that function both as a reflection of the way women are expected to perform as both gendered objects of beauty available to the patriarchal gaze of men, and as complicit possessors of whiteness. In one image, a white woman gazes tearfully into a mirror, perhaps in crisis about her own subjectivity. Of this image, philosopher George Yancy writes that white people should go home this evening and “take a long look in the mirror and pose this question: what in the hell makes whiteness, my whiteness, so special? By posing the question, they will begin to glimpse the insidious norm that is operating, perhaps they will see the lie that has functioned as the ‘truth’ for so long, the lie that returns them to themselves as ‘innocent’ and as disconnected from white supremacy.”

Buck Ellison

![]() Buck Ellison, The Prince Children, Holland, Michigan, 2019. Courtesy the artist and the Sunday Painter.

Buck Ellison, The Prince Children, Holland, Michigan, 2019. Courtesy the artist and the Sunday Painter.

Buck Ellison’s staged photographs study the signifiers of white American wealth — the social and political logic that underpins white supremacy. The subjects portrayed in this part documentary, part fiction could be any number of wealthy Americans who form an elite class of expensively educated individuals, proud of their success and the history of the USA. Is this a ‘perfect white family’, or is it a picture that contains and reports a number of questionable and humorous white appearances? In the form of a semi-formal group portrait, the photograph gives us a number of venerably posh signifiers: flowery upholstered furniture (traditional style); a large, welcoming fireplace fronted by a traditional rug (a warm and wholesome environment); plenty of pictures and books (knowledge is power); the boy wears his polo-neck tucked-in (smart, well bred) and the girls sit or stand in plaid skirts and knee-high hosiery (European cultural heritage, check).

John Lucas & Claudia Rankine

![]() John Lucas & Claudia Rankine, Stamped, 2018. Courtesy the artists.

John Lucas & Claudia Rankine, Stamped, 2018. Courtesy the artists.

John Lucas and Claudia Rankine’s Stamped works study the complexities of blond privilege in relationship to whiteness. The artists approached strangers on the street to ask them questions about their blondness, then photographed their hair. The images were then closely cropped and presented on postage stamps that frame blondness in terms of social value. The work asks, why, despite only 2% of the American population being naturally blond, do so many people choose to dye their hair a color that reflects whiteness, beauty and desirability? The answer may lie in the way that whiteness works unconsciously, promoting its continuation through subtle forms of symbolic representation that are here given visual life. Of the images, Rankine writes: “Can you separate the history of blondness in Europe from America? I don’t really think so. I think that it’s one story. And the most flagrant white supremacists in the United States are often referring back to European history in which these values were first institutionalized and used to justify genocide.”

Nancy Burson

![]() Nancy Burson, What If He Were: Black, 2018. Image courtesy the artist.

Nancy Burson, What If He Were: Black, 2018. Image courtesy the artist.

Nancy Burson’s digitally constructed portraits of Donald Trump portray the US president as various ‘races.’ The images were originally commissioned by a high profile magazine, which eventually decided not to publish them. Burson has been collaborating on the development of digital morphing technologies since the mid-1970s, and these new works see the artist hoping to understand what sort of empathy Trump might possess for people of color should he see these images of “himself” presented in various states of fictionalized biological difference.

This essay was published in edited form by the Guardian in December 2019 and serves as a brief introduction to my book The Image of Whiteness.

In what we now call ‘the West’, politics, business, justice, healthcare, education and culture are all white dominated. Whiteness is alive and well, yet we are seldom taught about its history. We white people are ignorant of a system we created, seeing ourselves as racially ‘neutral’ because we benefit from our own invention. Our bodies and minds are subject to social and psychological processes that interpellate us into whiteness. We internalize a false logic of racial difference, yet it has no biological or genetic basis. We take a social idea and allow it to govern how we live, and crucially, how we see. It is a myth that we live in ‘post-racial’ societies.

While understanding whiteness and race as social and legal inventions, I consider it important to understand whiteness as something nevertheless visual. White people ‘gaze,’ but we do not always see. Cultural theorist Stuart Hall called this the ‘white eye’. We whites are blind to the dominance of white visuality and we can understand this most clearly with the invention and popularization of photography, which is a visual world white people created in our own image.

What if the canonical history of photography — emerging in the 1830s some two-hundred years after whiteness — is best understood, not as an objective ‘history of pictures,’ but as a history of white visuality, even white visual racism? What if the camera is the logical extension of the white eye? After all, it’s not just the ‘race’ of the person who uses the camera that governs its way of gazing, it’s also the very materials used to make the pictures. What would it mean for whites, and white photographers, to accept that we see with a white racist eye? Furthermore, as the identity of whiteness was born out of a form of social violence, what if to be white is to be racist? I believe these are complex social and psychological questions that must be taken seriously if we are to create a truly fair and equal world. There is no good whiteness.

In order to untie ourselves from whiteness, and from white dominant photographic practices, we need to subvert what I call ‘the image of whiteness.’ This would be the very act of rendering ourselves open and vulnerable to the reality of whiteness, while at the same time attacking the logic of its image. Images are, after all, forms of imagination — so why can’t we imagine a world without whiteness, without white eyes?

In the hope that we might get there someday, let’s consider how contemporary photographic art on the subject of whiteness, in its varying subtleties and guises, can be put to use as a form of subversion, or disruption. A rebuttal to white visual culture. As Yasmin Gunaratnam has asked, how can photographic images “detain” or reveal whiteness? How might photography be reclaimed from its own history, in order to help white people see anew?

Michelle Dizon & Viêt Lê

Michelle Dizon & Viêt Lê, White Gaze (book spread), 2018. Courtesy the artists and Sming Sming Books.

Michelle Dizon & Viêt Lê, White Gaze (book spread), 2018. Courtesy the artists and Sming Sming Books.Michelle Dizon and Viêt Lê’s White Gaze bookproject sees the artists appropriate photographs from the National Geographic archive and put them to anti-racist use. The American magazine has a long history of racist visual overtones that place people of colour in a subjugated relationship to the ethnographic and imperial gaze of white western photographers. The artists juxtapose images with concrete poetry to create image-text intersections that reveal and critique visual cultures of whiteness, the white eye, and its forms of privileged looking. Of the project, Michelle Dizon writes: “There are certainly a lot of images where the camera is present, or where a white photographer took a picture within a specific context. Where there is looking, it’s usually a very gendered looking, and those forms of gendered violence across the bodies of both colonized women and men run throughout these images.”

Ken Gonzalez-Day

Ken Gonzales-Day, East First Street #2 (St. James Park), from the series Erased Lynchings, 2013. Courtesy the artist and Luis De Jesus Los Angeles.

Ken Gonzales-Day, East First Street #2 (St. James Park), from the series Erased Lynchings, 2013. Courtesy the artist and Luis De Jesus Los Angeles.Ken Gonzalez-Day’s images from the series Erased Lynchings sees the artist digitally remove the dead and hanging body of a nameless murdered person of colour, in order to avoid re-victimising the individual. This places our attention on the real guilty subjects, those white people who take it upon themselves extrajudicially to police Black and Brown bodies. The Black body is here removed from the gaze of white eyes, a form of sight which undergirds the social dominance of whiteness. Gonzales-Day writes on his website: “The work asks viewers to consider the crowd, the spectacle, the role of the photographer, and even the impact of flash photography, and their various contributions to our understanding of racialized violence in this Nation.”

Hank Willis Thomas

Hank Willis Thomas, Wipe Away the Years, 1932/2015, from the series Unbranded: A Century of White Women, 1915-2015. Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Hank Willis Thomas, Wipe Away the Years, 1932/2015, from the series Unbranded: A Century of White Women, 1915-2015. Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.Hank Willis Thomas’s works Unbranded: A Century of White Women, 1915-2015, are made by appropriating old advertisements and removing logos and text. What remains are images that function both as a reflection of the way women are expected to perform as both gendered objects of beauty available to the patriarchal gaze of men, and as complicit possessors of whiteness. In one image, a white woman gazes tearfully into a mirror, perhaps in crisis about her own subjectivity. Of this image, philosopher George Yancy writes that white people should go home this evening and “take a long look in the mirror and pose this question: what in the hell makes whiteness, my whiteness, so special? By posing the question, they will begin to glimpse the insidious norm that is operating, perhaps they will see the lie that has functioned as the ‘truth’ for so long, the lie that returns them to themselves as ‘innocent’ and as disconnected from white supremacy.”

Buck Ellison

Buck Ellison, The Prince Children, Holland, Michigan, 2019. Courtesy the artist and the Sunday Painter.

Buck Ellison, The Prince Children, Holland, Michigan, 2019. Courtesy the artist and the Sunday Painter.Buck Ellison’s staged photographs study the signifiers of white American wealth — the social and political logic that underpins white supremacy. The subjects portrayed in this part documentary, part fiction could be any number of wealthy Americans who form an elite class of expensively educated individuals, proud of their success and the history of the USA. Is this a ‘perfect white family’, or is it a picture that contains and reports a number of questionable and humorous white appearances? In the form of a semi-formal group portrait, the photograph gives us a number of venerably posh signifiers: flowery upholstered furniture (traditional style); a large, welcoming fireplace fronted by a traditional rug (a warm and wholesome environment); plenty of pictures and books (knowledge is power); the boy wears his polo-neck tucked-in (smart, well bred) and the girls sit or stand in plaid skirts and knee-high hosiery (European cultural heritage, check).

John Lucas & Claudia Rankine

John Lucas & Claudia Rankine, Stamped, 2018. Courtesy the artists.

John Lucas & Claudia Rankine, Stamped, 2018. Courtesy the artists.John Lucas and Claudia Rankine’s Stamped works study the complexities of blond privilege in relationship to whiteness. The artists approached strangers on the street to ask them questions about their blondness, then photographed their hair. The images were then closely cropped and presented on postage stamps that frame blondness in terms of social value. The work asks, why, despite only 2% of the American population being naturally blond, do so many people choose to dye their hair a color that reflects whiteness, beauty and desirability? The answer may lie in the way that whiteness works unconsciously, promoting its continuation through subtle forms of symbolic representation that are here given visual life. Of the images, Rankine writes: “Can you separate the history of blondness in Europe from America? I don’t really think so. I think that it’s one story. And the most flagrant white supremacists in the United States are often referring back to European history in which these values were first institutionalized and used to justify genocide.”

Nancy Burson

Nancy Burson, What If He Were: Black, 2018. Image courtesy the artist.

Nancy Burson, What If He Were: Black, 2018. Image courtesy the artist.

Nancy Burson’s digitally constructed portraits of Donald Trump portray the US president as various ‘races.’ The images were originally commissioned by a high profile magazine, which eventually decided not to publish them. Burson has been collaborating on the development of digital morphing technologies since the mid-1970s, and these new works see the artist hoping to understand what sort of empathy Trump might possess for people of color should he see these images of “himself” presented in various states of fictionalized biological difference.

This essay was published in edited form by the Guardian in December 2019 and serves as a brief introduction to my book The Image of Whiteness.