Pieces

of Me

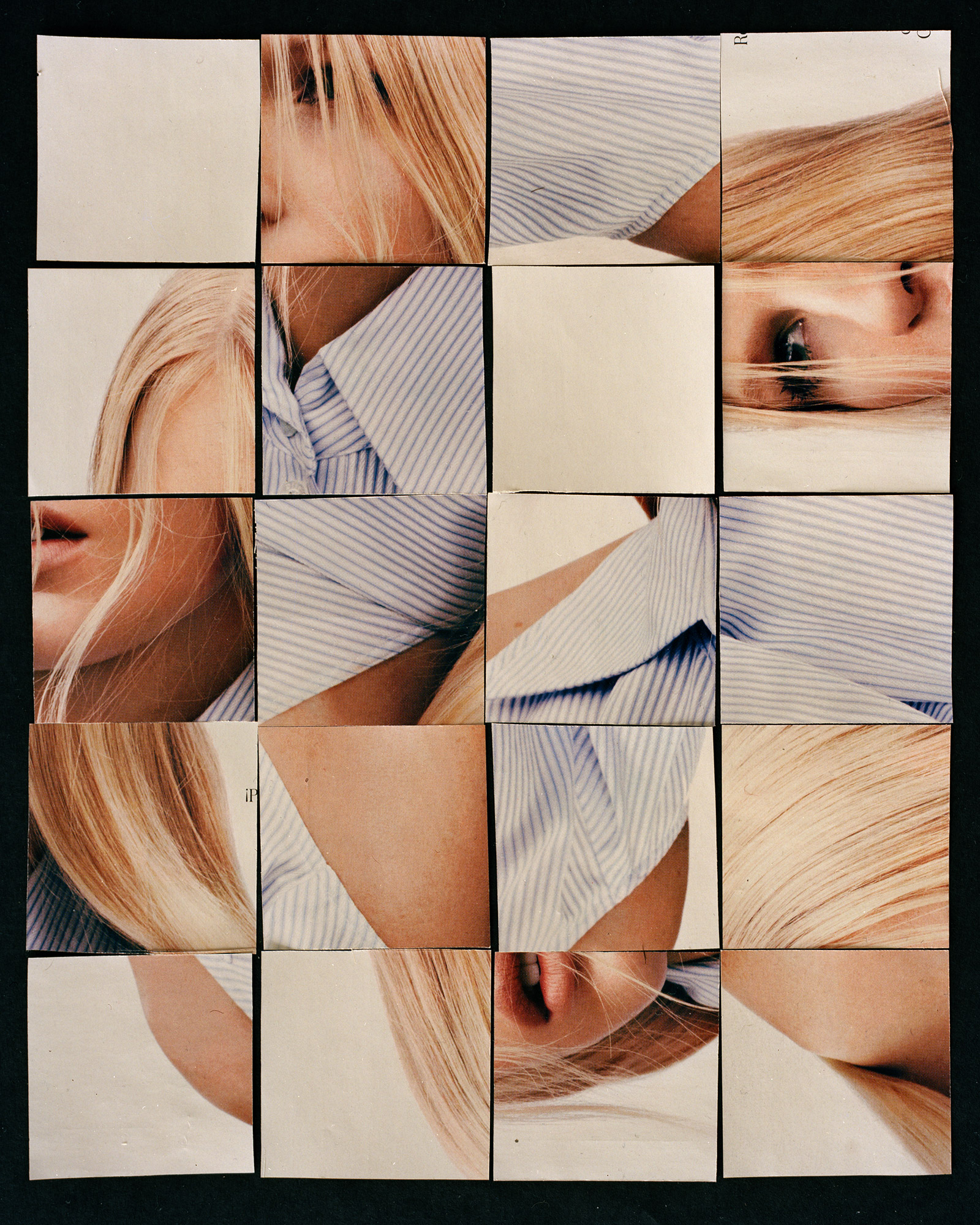

Louise Parker, Pieces of Me, 2016.

“Parker takes the subject and form of the female body and repurposes it into chopped and spliced composites that offer a critique of consumerism and the binary repetitions of the body-image as seen in the contemporary media.”

It is too often incorrectly stated that men invented photomontage. Canonical histories of the medium locate its origins in the Dada of John Heartfield, or the Constructivism of Aleksander Rodchenko. Patricia Allmer writes, in her 2016 essay Feminist Interventions: Revising the Canon, that Dada “tends to be evaluated within a self‐sustaining and overwhelmingly male critical tradition of exclusion… male artists exaggerate their importance to the canon, and often do so at the expense of their female colleagues.” Within almost an entire century’s history books written by established male art historians, and in the memoirs of famous male Dada artists, we witness the consistent downplaying of the role of women photomontagists. However politely, Ruth Hemus states in her 2009 book Dada’s Women that those ignored “did not fare well”. It’s an unfortunate if not cringing fact that it wasn’t until the 1980s that women Dadaists – including Sophie Taeuber, Hannah Höch and Céline Arnauld – appeared on the pages of established art history books, such are the foibles of the canon.

![]() Kate Edith Gough (1856–1948), Untitled page from the Gough Album, late 1870s. Collage of watercolor and albumen silver prints. V&A Images/Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Kate Edith Gough (1856–1948), Untitled page from the Gough Album, late 1870s. Collage of watercolor and albumen silver prints. V&A Images/Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Much earlier than Dada, as a 2010 Metropolitan Museum of Art New York exhibition makes clear, it was aristocratic English Victorian housewives in the 1860s and 70s that began collaging and montaging photographs. Kate Edith Gough’s photographs of women’s hatted heads attached to the watercolour-painted bodies of ducks in quaint pond scenes surrounded by tall-standing reeds, or the Countess of Yarborough Victoria Alexandrina Anderson-Pelham’s albumen photograph of a man’s head on a shrunken body, poking a fork into an empty pickle jar full of other like-montaged subjects, offer the art form some historical perspective, humorous and puckish as it is.

Louise Parker’s montages here take from a very particular and later tradition of women Dada artists that sought to more directly and subversively criticise the social status quo of the time. Like her predecessors, Parker takes the subject and form of the female body and repurposes it into chopped and spliced composites that offer a critique of consumerism and the binary repetitions of the body-image as seen in the contemporary media. Somewhat like Hannah Höch before her, Parker cuts and combines the photographic image into messy and light-hearted satire, and comments on the way in which advertisements aimed at women seek to reinforce the various tropes of feminine idealism. These ideas have no doubt surfaced through her own experience working as a fashion model. Parker has been photographed by celebutante contemporary art photographers Ryan McGinley and Roe Ethridge, i-D magazine referring to Parker as Ethridge’s ‘muse’ in an interview from 2015.

In Parker’s image above, a bunch of blonde hair (the ‘ideal’ hair colour?) is positioned next to a 12-inch ruler to indicate optimum, or perhaps normative, ponytail length. Around the hair, a green shiny ribbon is tied in a ‘girly’ bow just below where the bunch has been cut off. This cut is two-fold in its meaning, as it refers both to the physical act of cutting in montage itself and to the conceptual separation of the hair from the body, evoking the destruction of the feminine ideal. In a different sense, one image that represents a gender norm is graphically interrupted through its combining with other images that seek to controvert or displace it. Where Höch plays with gender ambiguity in her montage Dompteuse (Tamer)(c.1930), Parker instead works with the direct and specific satirical exaggeration of the feminine stereotype in her works.

In a self-portrait Höch pictures her enlarged head on a tiny body wielding a pair of scissors – the essential montagist’s object, be they analogue or digital. Both indispensable tool and art-historical motif, scissors or knives appear not just in Parker’s and Höch’s work, but often as metaphors in the wider history of visual art. A 1694 Baroque painting by the Frenchman Pierre Mignard pictures Time clipping Cupid’s wings; later Henri Matisse would refer to his cut-up technique as akin to ‘drawing with scissors’; and again in the twentieth century, Joe Tilson would picture scissors in his 1968 collage Cut Out and Send; as would Dieter Roth in his Seminar (1971), a collaboration with Richard Hamilton which saw visual elements layered and montaged. Alongside the knife, scissors, rarely a lone scissor – always plural – one blade pivoting with another – seem to communicate something essential to the practice of montage. As Truman Capote tell us, “I believe more in the scissors than the pencil.”

Parker’s works are an attestation to the critical power of the now-ubiquitous montaged image in contemporary culture, the importance of the historical role of women Dadaists, and to the ongoing use of key modernist image-making techniques – of which photomontage is one – in contemporary photography. This method of making photographic images still resonates more than one-hundred years after it began in the homes of Victorian women, in which they sought to find distraction from the dulling patriarchical repetitions of home and children. As Virginia Woolf writes, and to conclude with emphasis on the important history of critical thinking by women artists that surrounds conceptions of the body in art from the last decades of the nineteenth century to Dada and beyond, "I ask now, standing with my scissors among my flowers, where can the shadow enter? … I am sick of the body, I am sick of my own craft, industry and cunning, of the unscrupulous ways of the mother who protects, who collects under her jealous eyes at one long table her own children, always her own."

This essay was published by Foam magazine, Amsterdam, in September 2016 and was written to accompany Louise Parker's project Pieces of Me.

Kate Edith Gough (1856–1948), Untitled page from the Gough Album, late 1870s. Collage of watercolor and albumen silver prints. V&A Images/Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Kate Edith Gough (1856–1948), Untitled page from the Gough Album, late 1870s. Collage of watercolor and albumen silver prints. V&A Images/Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Much earlier than Dada, as a 2010 Metropolitan Museum of Art New York exhibition makes clear, it was aristocratic English Victorian housewives in the 1860s and 70s that began collaging and montaging photographs. Kate Edith Gough’s photographs of women’s hatted heads attached to the watercolour-painted bodies of ducks in quaint pond scenes surrounded by tall-standing reeds, or the Countess of Yarborough Victoria Alexandrina Anderson-Pelham’s albumen photograph of a man’s head on a shrunken body, poking a fork into an empty pickle jar full of other like-montaged subjects, offer the art form some historical perspective, humorous and puckish as it is.

Louise Parker’s montages here take from a very particular and later tradition of women Dada artists that sought to more directly and subversively criticise the social status quo of the time. Like her predecessors, Parker takes the subject and form of the female body and repurposes it into chopped and spliced composites that offer a critique of consumerism and the binary repetitions of the body-image as seen in the contemporary media. Somewhat like Hannah Höch before her, Parker cuts and combines the photographic image into messy and light-hearted satire, and comments on the way in which advertisements aimed at women seek to reinforce the various tropes of feminine idealism. These ideas have no doubt surfaced through her own experience working as a fashion model. Parker has been photographed by celebutante contemporary art photographers Ryan McGinley and Roe Ethridge, i-D magazine referring to Parker as Ethridge’s ‘muse’ in an interview from 2015.

In Parker’s image above, a bunch of blonde hair (the ‘ideal’ hair colour?) is positioned next to a 12-inch ruler to indicate optimum, or perhaps normative, ponytail length. Around the hair, a green shiny ribbon is tied in a ‘girly’ bow just below where the bunch has been cut off. This cut is two-fold in its meaning, as it refers both to the physical act of cutting in montage itself and to the conceptual separation of the hair from the body, evoking the destruction of the feminine ideal. In a different sense, one image that represents a gender norm is graphically interrupted through its combining with other images that seek to controvert or displace it. Where Höch plays with gender ambiguity in her montage Dompteuse (Tamer)(c.1930), Parker instead works with the direct and specific satirical exaggeration of the feminine stereotype in her works.

In a self-portrait Höch pictures her enlarged head on a tiny body wielding a pair of scissors – the essential montagist’s object, be they analogue or digital. Both indispensable tool and art-historical motif, scissors or knives appear not just in Parker’s and Höch’s work, but often as metaphors in the wider history of visual art. A 1694 Baroque painting by the Frenchman Pierre Mignard pictures Time clipping Cupid’s wings; later Henri Matisse would refer to his cut-up technique as akin to ‘drawing with scissors’; and again in the twentieth century, Joe Tilson would picture scissors in his 1968 collage Cut Out and Send; as would Dieter Roth in his Seminar (1971), a collaboration with Richard Hamilton which saw visual elements layered and montaged. Alongside the knife, scissors, rarely a lone scissor – always plural – one blade pivoting with another – seem to communicate something essential to the practice of montage. As Truman Capote tell us, “I believe more in the scissors than the pencil.”

Parker’s works are an attestation to the critical power of the now-ubiquitous montaged image in contemporary culture, the importance of the historical role of women Dadaists, and to the ongoing use of key modernist image-making techniques – of which photomontage is one – in contemporary photography. This method of making photographic images still resonates more than one-hundred years after it began in the homes of Victorian women, in which they sought to find distraction from the dulling patriarchical repetitions of home and children. As Virginia Woolf writes, and to conclude with emphasis on the important history of critical thinking by women artists that surrounds conceptions of the body in art from the last decades of the nineteenth century to Dada and beyond, "I ask now, standing with my scissors among my flowers, where can the shadow enter? … I am sick of the body, I am sick of my own craft, industry and cunning, of the unscrupulous ways of the mother who protects, who collects under her jealous eyes at one long table her own children, always her own."

This essay was published by Foam magazine, Amsterdam, in September 2016 and was written to accompany Louise Parker's project Pieces of Me.