Path to

Clouds

‘No mortals are there, but Clouds of the airgreat Gods who the indolent fill…’

— Socrates in Aristophanes’ The Clouds

Clouds might visualise a comic disclosure. Fluffy stratocumulus, in the title sequence of The Simpsons, part to reveal the show’s name in that familiar yellow cartoon skin tone. These clouds obscure and then suddenly reveal, somewhat like the manner in which the alcoholic and depressed Krusty the Clown appears from below camera into frame, finding enthusiasm for his children’s television show in compensation for the little he gets from life. Clouds are formed by Krusty’s smoking habit too. In one episode the TV studio fills with smoke. In another, Krusty temporarily quits, revealing a nicotine patch on his forearm to his audience of children: ‘So, this patch steadily releases nicotine into my body, eliminating my need for cigarettes.’ Then Krusty pauses for a moment, revealing something altogether more psychotic as he frantically licks at the patch in a fit of desperation and addiction. This is merely one example of many ways The Simpsons describes the world of comic discordance. Comedy is complex. Humour, as the American poet J. R. Lowell writes, ‘Is a perception of the incongruous.’

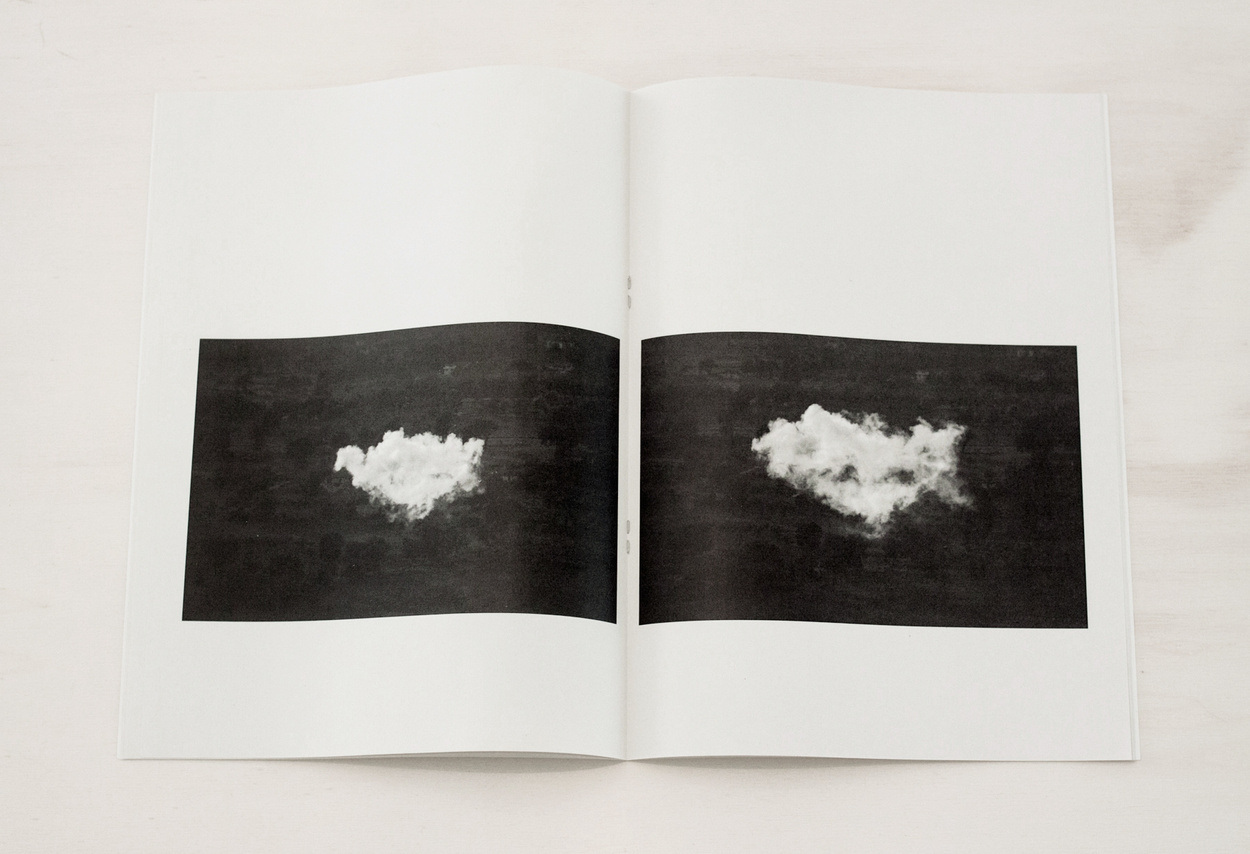

The appearance of single clouds in Massimiliano Rezza’s photographs offer their own incongruity. These clouds ask their viewer for an active response. As multiple and non-identical as clouds are, a single cloud seems uniformly irreconcilable with passive looking. A group of clouds can be ignored. A single cloud invites a return, activity — it’s loneliness offering it a character that companionship would not similarly evoke. Rezza suggests it’s time to pay attention to single clouds, but not with the sort of poetry one might anticipate.

In a few pictures clouds dissipate into the frame of the image from below or from the side. These are plumes of ambiguity — are they clouds or is it smoke? — that threaten to wash across the picture plain and remove its sense of height, perspective and depth. Clouds reveal the meaning of other things, as is the case with comic disclosure, but they also obfuscate their own meanings, as is the notion here with Rezza’s befogged compositions. Clouds are dead metaphors: their overuse in this way offers them both all the meaning in the world and none at all. A metaphor dies when we are no longer able to distinguish between its vehicle and its tenor, as the English writer I.A. Richards has it. From Aristophanes’ The Clouds (423BC) to John Durham Peters’ The Marvellous Clouds (2015), these floating collections of water droplets have been squeezed of all potential meaning — literary, technological, or otherwise. Before the internet, clouds carried a number of things: water, ice, metaphors abound. After the internet clouds are the things that carry all data. Everything is given over to clouds. Clouds have become The Cloud, a vast storage facility orchestrating the power of the vectorialist class; the owners of information in commodity form.

Clouds lose their humour in monotone — their ability to discreetly hide things away — and this is crucial to Rezza’s work. To photograph a cloud in black and white is to deaden it somehow; to accept its spent metaphorical potential and represent it as the inert thing that it is today. This is the success of Rezza’s photographs: they isolate single clouds so we might pay attention to them. The single cloud here becomes not the focus of poetry, but of politics: these clouds own all the water droplets and the growing plume of stratus — other, immigrant clouds – come into view, up from below 6,000 feet to take them back (ice, water, the means of production, conceptual metaphor). Let us not empathise with the loneliness of privileged clouds, but instead relieve them of their burdens by inviting the migrating cirrocumulus to take what is rightfully theirs.

Cesare Ballardini, Guardando in basso, 1997

Where Rezza Studies the allegorical potential of clouds above, Cesare Ballardini assumes the dictum of the lyrical in his work on the land, which sees the photographer walking and observing seemingly banal things in order to address an open process of poetics — a theory of forms — in which photography captures the necessarily political meaning of landscape. His are images tied to melancholy and to remembrance, but also importantly to a critical understanding of the differences between two types of space. What seems to be a simple walk to the beach, in fact revels in the relationship between visual and spatial conflict: the border between land and sea, habitable and uninhabitable territories — a path, a pattern, a place — at once figurative and abstract.

Rebecca Solnit states with regard to landscape devoid of human agency, ‘There is an interesting removal of the figure from the landscape, which generates anxieties.’ In Ballardini’s images we see a related phenomenon: a single photograph depicts his shadow, the direct representation of the human figure is removed from the landscape altogether, or simply reflected in the narrow makeshift pathways that form his walk from sandy shrubland to beach. It is first implied that this is the journey of a companionless photographer, but in fact all these images reveal the ubiquitous trace of multiple human presences. In this sense, although one might say ‘There are no people in the images,’ they are in fact full with humans. This is what renders these images both anxious and political: anxious because the presence of humans is spectral, implied by shadows and traces, and political due to the fact that, evidently, all things concerning human activity are so (not least the effect we have on the land we use, misuse, or indeed haunt).

Ballardini’s places become spaces in various subtle ways. This comes about through a consideration of space as abstract, and place as imbued with meanings, representations, figurations. Perhaps the photographer allows for a certain movement between these two things, inasmuch as the images are both empty and occupied. In her On Anxiety (2004), Renata Salecl writes ‘When we are told that we live in an age of anxiety… this is related to the proliferation of possible catastrophes.’ Stemming from capitalism, social anxiety is all-pervading. But what of the photographic image of anxiety? Ballardini takes this idea at a slant: the semblance of human presence, in the creation of a path, or with the appearance of a shadow, causes an anxiety of forms. The recognisable or figurative elements of his pictures collide with textured abstractions. Dry grass blends with sand; a metal swing-gate casts a shadow adding a slicing, formalist line across the image; the surface of waves ripple water into unrecognisable shapes. Here, catastrophe is manifested in an approximation of human presence. Mankind’s effect on the earth creates rising sea levels, which in turn will conjoin the water with areas of shrubland such as those Ballardini pictures. All human presence ends in catastrophe, so it would seem.

Achille Filipponi, Der Strom, 2011

Achille Filipponi, Der Strom, 2011

Achille Filipponi, Der Strom, 2011

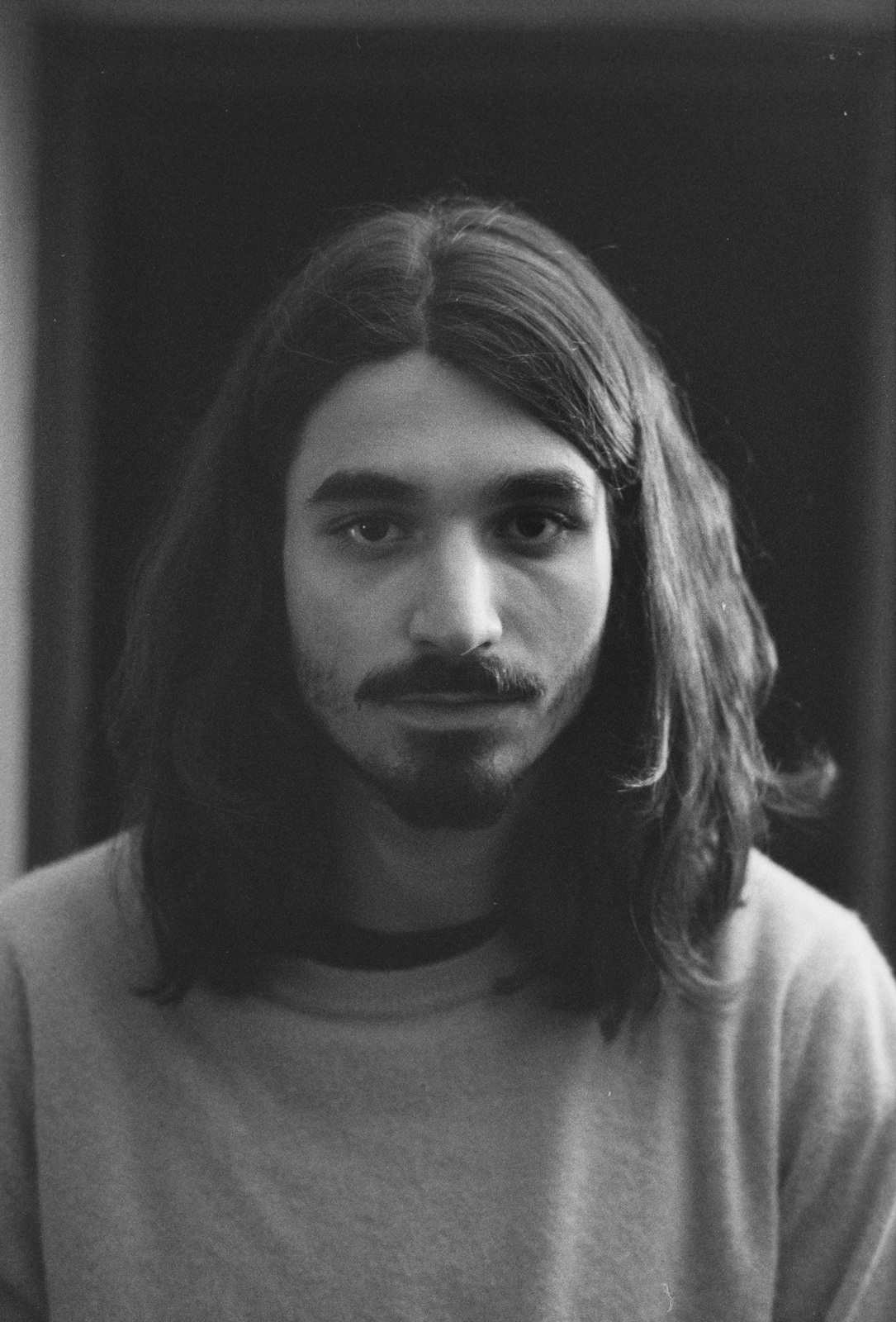

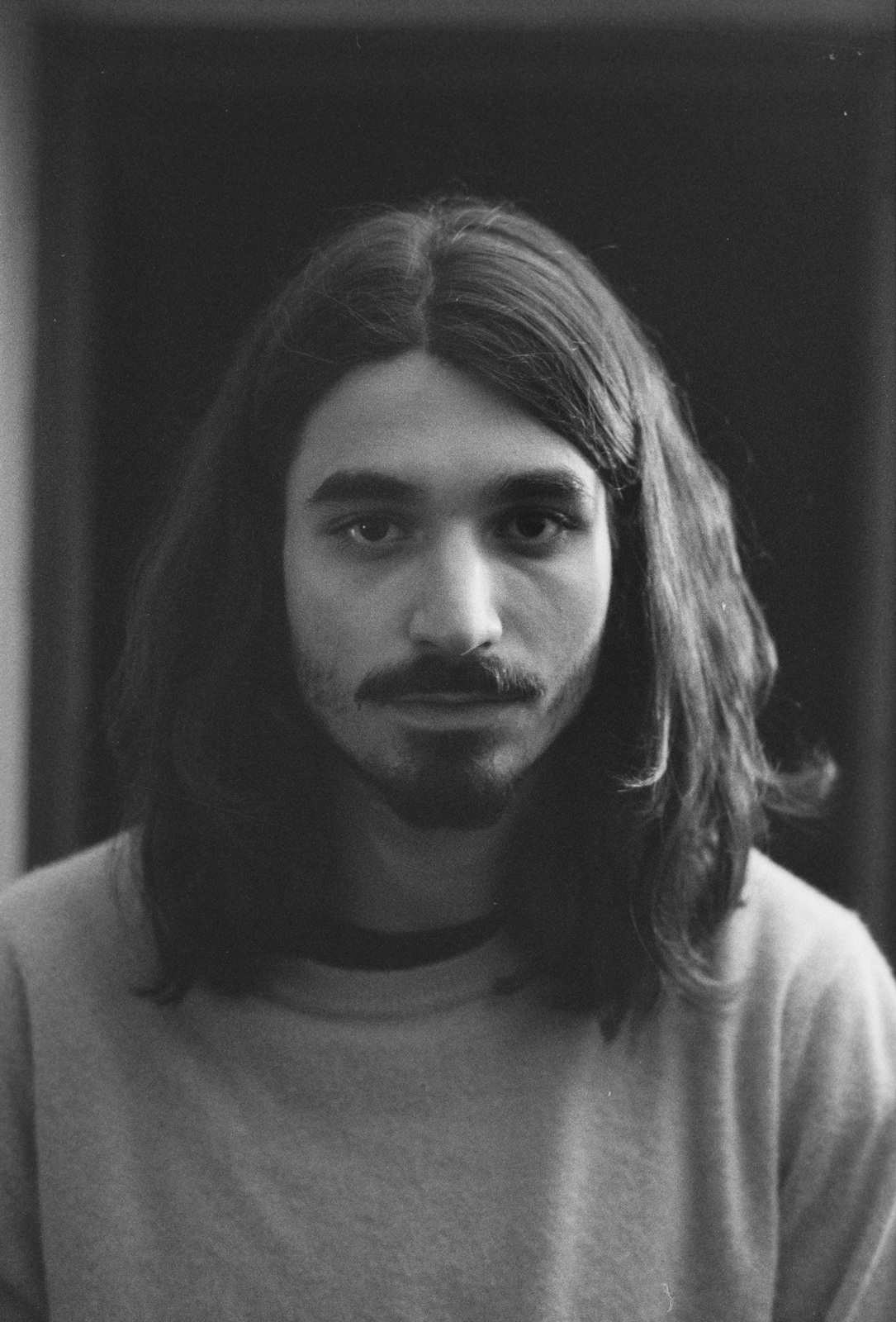

Achille Filipponi’s two portraits form the series Der Strom (The Stream) bring a form of anxiety to the subject of aging. In this sense they bookend the other works here, offering time up as the subject of catastrophe par excellence. In one, the face of a young man stares neutrally back at the camera. In a second photograph, the subject — Claudio, the older brother of the young Marco — represents the path to maturity with a different type of “neutral” gaze.

In Aging and Identity: Some Reflections on the Somatization of the Self (2015), Bryan S. Turner writes that the sociology of aging can be described in the ‘Contradictory relationship between the subjective sense of an inner youthfulness and an exterior process of biological aging.’ Filipponi’s photographs visualise this contradiction, placing another form of incongruity at the centre of photography’s relationship to age. As Nietzsche writes: ‘Existence is only an uninterrupted having been, a thing which lives by denying itself, consuming itself, and contradicting itself.’ Contradiction and the unwitting denial of age may be at the centre of the photographic representation of aging, but of course the neutral gaze of our subjects here don’t necessarily reveal that, unless we trick the photograph somehow...

Susan Sontag calls photography an ‘Elegiac art’. The Sontagian photographic image is a song; a threnody of aging, dying and death. After Nietzsche, such statements on the photographic image sound a cliché. What might silence offer us instead? In the silence of a photograph there lies an anxiety. In Franz Kafka’s short story The Silence of the Sirens (1931), it is explained that the silence of the Sirens is more deadly than their song. Sontag’s “orchestral melancholy” — in which the word elegiac finds a synonym — renders photography too noisy, as if it is only capable of song. Kafka says the Sirens fell silent when they saw the look of ‘Innocent elation’ on Ulysses’ face. With ears stuffed with wax, Ulysses couldn’t hear whether the Sirens were singing or not, which is what we see in visual terms in Filipponi’s portraits here: we don’t know whether the two subjects are considering age, but we do know silence greets them and forms the paradoxical relationship between inner youthfulness and bodily aging. Like the Sirens’ surprise at Ulysses’ elation, we call the photograph’s bluff by feigning deafness, or, put another way, blind deafness: a manner of waiting for the photograph to sing, all the while knowing that it won’t. Once we discover the cliché of photography’s threnody on death we can call its bluff this way. Then photography becomes a silent enterprise; a deaf vessel incapable of song. The Sontagian metaphor for photography as an elegiac art ceases to be.

One dead metaphor used for describing aging, and indeed life lived, is that one must take one’s own path. This is destiny, existence, as aphorism: ‘Peruse your path’ says Henry David Thoreau, ‘We must ourselves take the path’ says Siddhārtha Gautama, ‘As people are walking all the time, in the same spot, a path appears’ writes the Enlightenment philosopher John Locke. In the present time all our paths are bound to information, digital identity — portraits of ourselves — uploaded to networked space. Today we walk a path to clouds, seeking out personal meaning, and failing to form community at the sort of level that might enact political change.

In the way in which, as M. H. Abrams writes, ‘The lyric genre comprehends a variety of utterances’, our current cloud formations conversely turn individuality into homogeneity. Unlike the literary genre of the lyric, our “musings in solitude” fail to transpire when they are commodified and fed back to us in the form of targeted advertisements. We might instead turn dead metaphors into conceptual ones. As Blanco and Peeren suggest, ‘A conceptual metaphor differs from an ordinary one in evoking, through a dynamic comparative interaction, not just another thing, word or idea and its associations, but a discourse, a system of producing knowledge.’ This is Filipponi’s sentiment: age transforms images into “a stream” of quiet neutrality, dead metaphors abound. We must stop photographing our own faces and offer the vectorialist class images of our shadows instead. Shadows, as silent utterances, slowly forming knowledge – a discourse that might emancipate clouds.

This essay was published in the catalogue Periodo Ipotetico, published alongside an exhibition of the same name at T14 Contemporary, Milan, in 2017.

The appearance of single clouds in Massimiliano Rezza’s photographs offer their own incongruity. These clouds ask their viewer for an active response. As multiple and non-identical as clouds are, a single cloud seems uniformly irreconcilable with passive looking. A group of clouds can be ignored. A single cloud invites a return, activity — it’s loneliness offering it a character that companionship would not similarly evoke. Rezza suggests it’s time to pay attention to single clouds, but not with the sort of poetry one might anticipate.

In a few pictures clouds dissipate into the frame of the image from below or from the side. These are plumes of ambiguity — are they clouds or is it smoke? — that threaten to wash across the picture plain and remove its sense of height, perspective and depth. Clouds reveal the meaning of other things, as is the case with comic disclosure, but they also obfuscate their own meanings, as is the notion here with Rezza’s befogged compositions. Clouds are dead metaphors: their overuse in this way offers them both all the meaning in the world and none at all. A metaphor dies when we are no longer able to distinguish between its vehicle and its tenor, as the English writer I.A. Richards has it. From Aristophanes’ The Clouds (423BC) to John Durham Peters’ The Marvellous Clouds (2015), these floating collections of water droplets have been squeezed of all potential meaning — literary, technological, or otherwise. Before the internet, clouds carried a number of things: water, ice, metaphors abound. After the internet clouds are the things that carry all data. Everything is given over to clouds. Clouds have become The Cloud, a vast storage facility orchestrating the power of the vectorialist class; the owners of information in commodity form.

Clouds lose their humour in monotone — their ability to discreetly hide things away — and this is crucial to Rezza’s work. To photograph a cloud in black and white is to deaden it somehow; to accept its spent metaphorical potential and represent it as the inert thing that it is today. This is the success of Rezza’s photographs: they isolate single clouds so we might pay attention to them. The single cloud here becomes not the focus of poetry, but of politics: these clouds own all the water droplets and the growing plume of stratus — other, immigrant clouds – come into view, up from below 6,000 feet to take them back (ice, water, the means of production, conceptual metaphor). Let us not empathise with the loneliness of privileged clouds, but instead relieve them of their burdens by inviting the migrating cirrocumulus to take what is rightfully theirs.

Cesare Ballardini, Guardando in basso, 1997

Where Rezza Studies the allegorical potential of clouds above, Cesare Ballardini assumes the dictum of the lyrical in his work on the land, which sees the photographer walking and observing seemingly banal things in order to address an open process of poetics — a theory of forms — in which photography captures the necessarily political meaning of landscape. His are images tied to melancholy and to remembrance, but also importantly to a critical understanding of the differences between two types of space. What seems to be a simple walk to the beach, in fact revels in the relationship between visual and spatial conflict: the border between land and sea, habitable and uninhabitable territories — a path, a pattern, a place — at once figurative and abstract.

Rebecca Solnit states with regard to landscape devoid of human agency, ‘There is an interesting removal of the figure from the landscape, which generates anxieties.’ In Ballardini’s images we see a related phenomenon: a single photograph depicts his shadow, the direct representation of the human figure is removed from the landscape altogether, or simply reflected in the narrow makeshift pathways that form his walk from sandy shrubland to beach. It is first implied that this is the journey of a companionless photographer, but in fact all these images reveal the ubiquitous trace of multiple human presences. In this sense, although one might say ‘There are no people in the images,’ they are in fact full with humans. This is what renders these images both anxious and political: anxious because the presence of humans is spectral, implied by shadows and traces, and political due to the fact that, evidently, all things concerning human activity are so (not least the effect we have on the land we use, misuse, or indeed haunt).

Ballardini’s places become spaces in various subtle ways. This comes about through a consideration of space as abstract, and place as imbued with meanings, representations, figurations. Perhaps the photographer allows for a certain movement between these two things, inasmuch as the images are both empty and occupied. In her On Anxiety (2004), Renata Salecl writes ‘When we are told that we live in an age of anxiety… this is related to the proliferation of possible catastrophes.’ Stemming from capitalism, social anxiety is all-pervading. But what of the photographic image of anxiety? Ballardini takes this idea at a slant: the semblance of human presence, in the creation of a path, or with the appearance of a shadow, causes an anxiety of forms. The recognisable or figurative elements of his pictures collide with textured abstractions. Dry grass blends with sand; a metal swing-gate casts a shadow adding a slicing, formalist line across the image; the surface of waves ripple water into unrecognisable shapes. Here, catastrophe is manifested in an approximation of human presence. Mankind’s effect on the earth creates rising sea levels, which in turn will conjoin the water with areas of shrubland such as those Ballardini pictures. All human presence ends in catastrophe, so it would seem.

Achille Filipponi, Der Strom, 2011

Achille Filipponi, Der Strom, 2011

Achille Filipponi, Der Strom, 2011 Achille Filipponi’s two portraits form the series Der Strom (The Stream) bring a form of anxiety to the subject of aging. In this sense they bookend the other works here, offering time up as the subject of catastrophe par excellence. In one, the face of a young man stares neutrally back at the camera. In a second photograph, the subject — Claudio, the older brother of the young Marco — represents the path to maturity with a different type of “neutral” gaze.

In Aging and Identity: Some Reflections on the Somatization of the Self (2015), Bryan S. Turner writes that the sociology of aging can be described in the ‘Contradictory relationship between the subjective sense of an inner youthfulness and an exterior process of biological aging.’ Filipponi’s photographs visualise this contradiction, placing another form of incongruity at the centre of photography’s relationship to age. As Nietzsche writes: ‘Existence is only an uninterrupted having been, a thing which lives by denying itself, consuming itself, and contradicting itself.’ Contradiction and the unwitting denial of age may be at the centre of the photographic representation of aging, but of course the neutral gaze of our subjects here don’t necessarily reveal that, unless we trick the photograph somehow...

‘Waiting for the photograph to sing, all the while knowing that it won’t.’

Susan Sontag calls photography an ‘Elegiac art’. The Sontagian photographic image is a song; a threnody of aging, dying and death. After Nietzsche, such statements on the photographic image sound a cliché. What might silence offer us instead? In the silence of a photograph there lies an anxiety. In Franz Kafka’s short story The Silence of the Sirens (1931), it is explained that the silence of the Sirens is more deadly than their song. Sontag’s “orchestral melancholy” — in which the word elegiac finds a synonym — renders photography too noisy, as if it is only capable of song. Kafka says the Sirens fell silent when they saw the look of ‘Innocent elation’ on Ulysses’ face. With ears stuffed with wax, Ulysses couldn’t hear whether the Sirens were singing or not, which is what we see in visual terms in Filipponi’s portraits here: we don’t know whether the two subjects are considering age, but we do know silence greets them and forms the paradoxical relationship between inner youthfulness and bodily aging. Like the Sirens’ surprise at Ulysses’ elation, we call the photograph’s bluff by feigning deafness, or, put another way, blind deafness: a manner of waiting for the photograph to sing, all the while knowing that it won’t. Once we discover the cliché of photography’s threnody on death we can call its bluff this way. Then photography becomes a silent enterprise; a deaf vessel incapable of song. The Sontagian metaphor for photography as an elegiac art ceases to be.

One dead metaphor used for describing aging, and indeed life lived, is that one must take one’s own path. This is destiny, existence, as aphorism: ‘Peruse your path’ says Henry David Thoreau, ‘We must ourselves take the path’ says Siddhārtha Gautama, ‘As people are walking all the time, in the same spot, a path appears’ writes the Enlightenment philosopher John Locke. In the present time all our paths are bound to information, digital identity — portraits of ourselves — uploaded to networked space. Today we walk a path to clouds, seeking out personal meaning, and failing to form community at the sort of level that might enact political change.

In the way in which, as M. H. Abrams writes, ‘The lyric genre comprehends a variety of utterances’, our current cloud formations conversely turn individuality into homogeneity. Unlike the literary genre of the lyric, our “musings in solitude” fail to transpire when they are commodified and fed back to us in the form of targeted advertisements. We might instead turn dead metaphors into conceptual ones. As Blanco and Peeren suggest, ‘A conceptual metaphor differs from an ordinary one in evoking, through a dynamic comparative interaction, not just another thing, word or idea and its associations, but a discourse, a system of producing knowledge.’ This is Filipponi’s sentiment: age transforms images into “a stream” of quiet neutrality, dead metaphors abound. We must stop photographing our own faces and offer the vectorialist class images of our shadows instead. Shadows, as silent utterances, slowly forming knowledge – a discourse that might emancipate clouds.

This essay was published in the catalogue Periodo Ipotetico, published alongside an exhibition of the same name at T14 Contemporary, Milan, in 2017.