Claimed Memories

of Previous Lives

‘The artist’s work, and the practice and identity of photography specifically, lends itself metaphorically to the tripartite concept of reincarnation.’

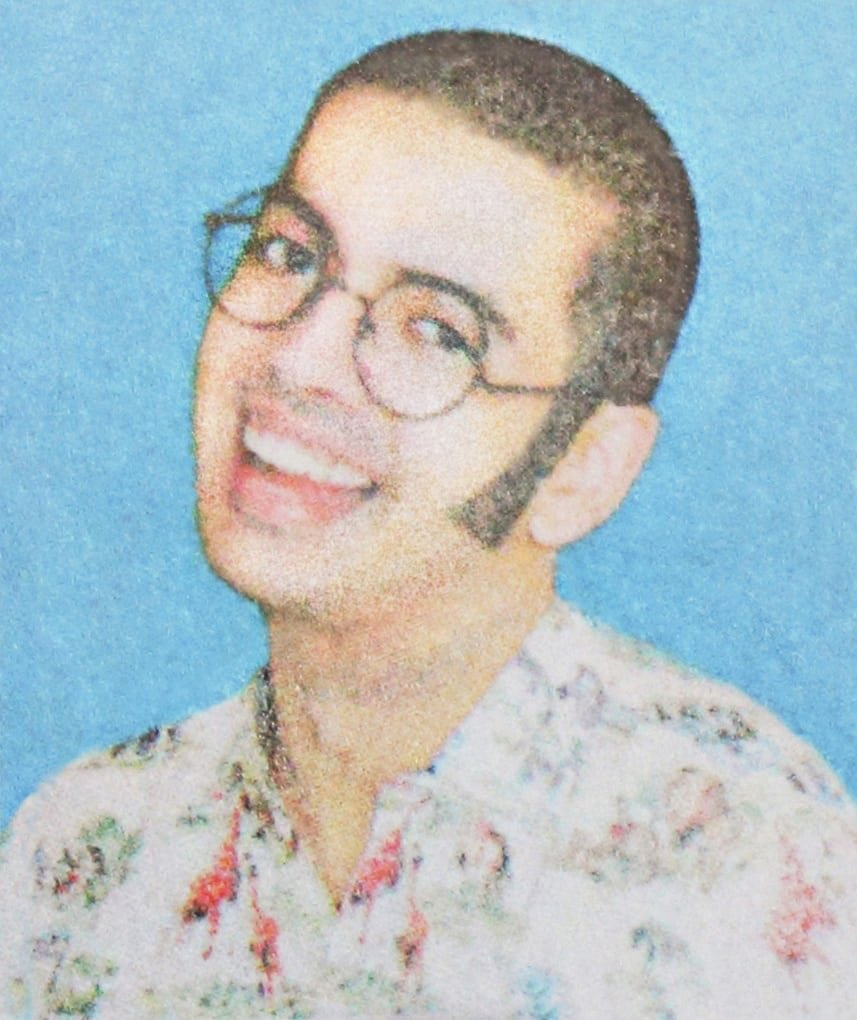

Sushant Chhabria cuts out portraits of the deceased from newspaper obituaries and recycles their faces, offering them new life. The digitally manipulated and combined features of the dead form new identities which, as the artist writes, ‘may or may not exist in the world.’ Spliced and tinkered with, these images transform old features into new physiognomies, often to strange, cartoon-like effect.

Alongside surface level humour, something eternal haunts Chhabria’s thinking, inflecting these portraits with an ineffability and mysticism. Between 2013-16, the artist ‘experimented with his own life,’ looking for meaning in the boredom and restlessness he was experiencing. Chhabria speaks of spending time flicking through newspapers, reading books or watching YouTube videos of Hindu, Buddhist and Zen teachings, searching around to invite cosmic order and discipline into his personal encounter with the world.

One day, while lying in bed with nothing to do, the artist came to compare his photographic process to reincarnation: like the manner in which, following the biological death of one body, souls take up residence in another, these portraits are created so that transmigrated beings might be born anew, confined to the strange anatomy of the photograph. In contrast to the process of collaging and recombining images of the body, ‘the soul can never be cut to pieces by any weapon, nor burned by fire, nor moistened by water, nor withered by the wind,’ says Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita, a Hindu scripture from the 4th or 5th Century BCE in which Chhabria sought solace regularly when making these images.

In loving memory of is an homage to the lifeless. It binds image to body through the soul as a kind of metaphor. A metaphor because, although there is little evidence that the soul exists in actuality, it forms a central part of the spiritual understanding of life for the artist. While Chhabria sees virtue in a life lived spiritually, he hasn’t, as he writes, ‘opened any of those books or videos for a long time and if I ever do, it won't be to fill the emptiness in me, but for the sake of their beauty.’ In this sense Chhabria’s personal relationship to the concept of reincarnation is an allegory for personal and artistic growth; one tied to various complex philosophical practices including yoga, which he began while undertaking this project.

In his 2000 study The phenomenon of claimed memories of previous lives: possible interpretations and importance, published by the journal Medical Hypotheses, Ian Stevenson writes: ‘The only systematic survey yet undertaken, one conducted in a region of northern India, showed that only about 1 person in 500 claimed to remember a previous life.’ In the “West,” reincarnation is incorrectly seen largely as a religious concept tied to the East, our scientific rationalism having little sympathy for its form of relatively esoteric thinking. However, Stevenson, until his death Professor of Psychology at the University of Virginia, had different beliefs, convinced as he was that reincarnation was a thing worth believing in, and furthermore, a scientifically provable phenomenon.

As the writer Thomas McEvilly notes in The Shape of Ancient Thought: Comparative Studies in Greek and Indian Philosophy (2001), reincarnation, although usually associated with India, was also a commonplace teaching of many Greek philosophers. Lest we Other the concept of reincarnation, we could do well to explore its roots for the culturally ubiquitous thing that they are – Saṃsāra in Sanskrit and metempsychosis in Greek, two linguistic testaments to the concept’s geographical plurality.

Referred to by McEvilly as The Doctrine of Reincarnation, the similarities between the concept of rebirth in Indian and Greek philosophy can be described in a cycle of three ideas. First, the aforementioned naming of the process in Sanskrit and Greek; second, the moral and cognitive laws governing the process (Sanskrit karma, Greek katharsis); and third, the goal of escape from the process (Sanskrit mokṣa, Greek lusis). As the Austrian writer Theodore Gomperz wrote in his The Greek Thinkers of 1920, there is an ‘agreement between Pythagorism and the Indian doctrine, not merely in their general features, but even in certain details, such as vegetarianism; and it may be added that the formulae which summarize the whole creed of the “circle and wheel”, of rebirths, are likewise the same in both.’

This process is reflected in Chhabria’s experience of seeking out meaning in his life. The artist’s work, and the practice and identity of photography specifically, lends itself metaphorically to the tripartite concept of reincarnation. The Ancient Greek and Indian philosophical comparability where the transmigration of the soul is concerned, base’s itself on a certain moral polarity. Souls are not randomly reborn in new bodies, but are instead rebirthed only if the subject recently dead lived a virtuous life. In verse 10 line 7 of the Chāndogyopaniṣad, the Hindu teacher writes:

This familiar homily describes the contrast, or polarity, between good and evil, positive and negative. The making of photographic images, as Chhabria knows, lends itself well to metaphorise spiritual practice through its own visual connection to this world of contrasts. These “positive” portraits see virtuous new lives offered to their subjects, and as he hasn’t read or watched a lecture on the Bhagavad Gita since completing the project in 2016, perhaps Chhabria has found his mokṣa or lusis – his escape from the process – and can now rest fulfilled until his next interesting body of work sparks off another necessary numinous crisis. The image captioned Traveller no. 09 is the artist’s self-portrait, and thusly his own conceptual reincarnation into the corpus of his work.

This essay was published by Foam in 2018.

Alongside surface level humour, something eternal haunts Chhabria’s thinking, inflecting these portraits with an ineffability and mysticism. Between 2013-16, the artist ‘experimented with his own life,’ looking for meaning in the boredom and restlessness he was experiencing. Chhabria speaks of spending time flicking through newspapers, reading books or watching YouTube videos of Hindu, Buddhist and Zen teachings, searching around to invite cosmic order and discipline into his personal encounter with the world.

One day, while lying in bed with nothing to do, the artist came to compare his photographic process to reincarnation: like the manner in which, following the biological death of one body, souls take up residence in another, these portraits are created so that transmigrated beings might be born anew, confined to the strange anatomy of the photograph. In contrast to the process of collaging and recombining images of the body, ‘the soul can never be cut to pieces by any weapon, nor burned by fire, nor moistened by water, nor withered by the wind,’ says Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita, a Hindu scripture from the 4th or 5th Century BCE in which Chhabria sought solace regularly when making these images.

In loving memory of is an homage to the lifeless. It binds image to body through the soul as a kind of metaphor. A metaphor because, although there is little evidence that the soul exists in actuality, it forms a central part of the spiritual understanding of life for the artist. While Chhabria sees virtue in a life lived spiritually, he hasn’t, as he writes, ‘opened any of those books or videos for a long time and if I ever do, it won't be to fill the emptiness in me, but for the sake of their beauty.’ In this sense Chhabria’s personal relationship to the concept of reincarnation is an allegory for personal and artistic growth; one tied to various complex philosophical practices including yoga, which he began while undertaking this project.

In his 2000 study The phenomenon of claimed memories of previous lives: possible interpretations and importance, published by the journal Medical Hypotheses, Ian Stevenson writes: ‘The only systematic survey yet undertaken, one conducted in a region of northern India, showed that only about 1 person in 500 claimed to remember a previous life.’ In the “West,” reincarnation is incorrectly seen largely as a religious concept tied to the East, our scientific rationalism having little sympathy for its form of relatively esoteric thinking. However, Stevenson, until his death Professor of Psychology at the University of Virginia, had different beliefs, convinced as he was that reincarnation was a thing worth believing in, and furthermore, a scientifically provable phenomenon.

As the writer Thomas McEvilly notes in The Shape of Ancient Thought: Comparative Studies in Greek and Indian Philosophy (2001), reincarnation, although usually associated with India, was also a commonplace teaching of many Greek philosophers. Lest we Other the concept of reincarnation, we could do well to explore its roots for the culturally ubiquitous thing that they are – Saṃsāra in Sanskrit and metempsychosis in Greek, two linguistic testaments to the concept’s geographical plurality.

Referred to by McEvilly as The Doctrine of Reincarnation, the similarities between the concept of rebirth in Indian and Greek philosophy can be described in a cycle of three ideas. First, the aforementioned naming of the process in Sanskrit and Greek; second, the moral and cognitive laws governing the process (Sanskrit karma, Greek katharsis); and third, the goal of escape from the process (Sanskrit mokṣa, Greek lusis). As the Austrian writer Theodore Gomperz wrote in his The Greek Thinkers of 1920, there is an ‘agreement between Pythagorism and the Indian doctrine, not merely in their general features, but even in certain details, such as vegetarianism; and it may be added that the formulae which summarize the whole creed of the “circle and wheel”, of rebirths, are likewise the same in both.’

This process is reflected in Chhabria’s experience of seeking out meaning in his life. The artist’s work, and the practice and identity of photography specifically, lends itself metaphorically to the tripartite concept of reincarnation. The Ancient Greek and Indian philosophical comparability where the transmigration of the soul is concerned, base’s itself on a certain moral polarity. Souls are not randomly reborn in new bodies, but are instead rebirthed only if the subject recently dead lived a virtuous life. In verse 10 line 7 of the Chāndogyopaniṣad, the Hindu teacher writes:

Those whose conduct here has been good will quickly attain a good birth … But those whose conduct here has been evil will quickly attain an evil birth…

This familiar homily describes the contrast, or polarity, between good and evil, positive and negative. The making of photographic images, as Chhabria knows, lends itself well to metaphorise spiritual practice through its own visual connection to this world of contrasts. These “positive” portraits see virtuous new lives offered to their subjects, and as he hasn’t read or watched a lecture on the Bhagavad Gita since completing the project in 2016, perhaps Chhabria has found his mokṣa or lusis – his escape from the process – and can now rest fulfilled until his next interesting body of work sparks off another necessary numinous crisis. The image captioned Traveller no. 09 is the artist’s self-portrait, and thusly his own conceptual reincarnation into the corpus of his work.

This essay was published by Foam in 2018.